Do you remember how the whole Internet thing started? I certainly do. I was a child when my father brought a personal computer to our tiny post-soviet apartment. It was a considerable investment for our family, but my father just shook it off, saying, “Marina, this is how the future looks like.” Then there was an era of computer games, dial-up connections, numerous quirky chat rooms, the rise of websites like MSN, Slate, search engines like AltaVista, Yahoo, and Google. It was a fascinating new world and an open door to other cultures, languages, countries. It’s hard to believe that some of those things were created from under the table in the basement somewhere in the San Francisco Bay Area by nerdy but passionate souls. These are the books about those people and the place they have created. From the very early days of Silicon Valley to its present modern state.

The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story | Michael Lewis (1999)

How the Internet Happened: From Netscape to the iPhone | Brian McCullough (2018)

Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future | Peter Thiel (2014)

Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup | John Carreyrou (2018)

Stealing Fire: How Silicon Valley, the Navy SEALs, and Maverick Scientists Are Revolutionizing the Way We Live and Work | Steven Kotler & Jamie Wheal (2017)

The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story | Michael Lewis (1999)

This is the oldest book on our list. We promise everything else in this article would be almost fresh out of the oven.

The reason we’ve included the book here is that it tells a riveting story about the onset of a “Silicon Valley phenomenon.” During the second half of the 90s, Silicon Valley became the center of the technological progress in the US, and consequently for the rest of the world. Technogeeks suddenly had an amazing business opportunity unfathomable to them before: nerdy coders, a taciturn bunch, could finally come out from their basements, build companies and make billions of dollars out in the open. Lewis’s story, in particular, shares the adventures of one of those technogeeks, Jim Clark, a to-be-founder of Netscape and two other billion-dollar companies, a quirky computer scientist who struck it rich or, perhaps, just happened to be at the right place at the right time.

The tone of the narrative, however, after almost two decades from the book’s publication, can be perceived as overly optimistic, which is completely understandable, provided it was written before the burst of the dot-com bubble, and the author had not yet seen the consequences of irrational exuberance, which he seemed to be fascinated with and trying to propagate.

Consider this passage, for example: “These people were the wealth creators. Their recipes were wealth. Electricity. The transistor. The microprocessor. The personal computer. The Internet. It followed from the theory that any society that wanted to become richer would encourage the traits, however bizarre, that led people to create new recipes… Qualities that … might have been viewed as antisocial, or even criminal, would be rewarded, honored, and emulated, simply because they led to more… recipes.”

Michael Lewis, a renowned investigative journalist, paints his own baroque picture of the central character; Jim Clark is portrayed as both a locus and a foil for every other successful entrepreneur of the Silicon Valley. Clark is more of a risk man than an idea man, although it just so happened that every risk he undertook was a prominent success.

Lewis, however, even though he obviously seemed deeply fond of his protagonist, still manages to provide insightful examples of how the companies were run back in the day or how they managed to stay afloat without any clear business model. For example, the author describes an incident when McCracken takes over Clark’s company and discovers that it doesn’t have a real budget plan or that the company spends almost two million a month and has three more months to live if such expenditure continues. Guess what does McCracken decide to do? He arranges psychological therapy classes for the whole team. That sounds a little redundant, don’t you think?

It’s of utmost pity, however, that Lewis spends so little time relating the story behind Netscape, apart from a few paragraphs mentioning Bill Gates’ famous memo to his employees acknowledging that the Internet poses the greatest threat to Microsoft.

Conversely, though, Lewis was more lenient and eloquent in his narration of Healtheon, which is now known as WebMD, a company Clark came up with during his regular visits to the hospital for treatment of blood disease.

The reason for Clark to hop from one idea to the next is partly explained by Lewis as fear of someone else catching up and buying out or dismantling his business. This is probably why you don’t really feel much empathy for the main character who at times can be seen as a “kamikaze” investor.

There’s another interesting observation about the 90s and the formation of Silicon Valley: thousands of smart Indian programmers had compensated for the US lack of tech talent back in the day, and the book partly shares some of those boys’ stories. These guys were working their necks off to leave from the “third world hellholes” and sucked for every possible opportunity that the tech world promised. How these young boys grabbed for their dreams makes for a truly fascinating and inspiring read.

How the Internet Happened: From Netscape to the iPhone | Brian McCullough (2018)

Perhaps, if you’re looking for a definitive and ultimate history book of the Internet, then look no further. How the Internet Happened tells the whole story and paints a complete picture of the rise of internet technologies: from the early days of Netscape to the unconditional dominance of the iPhone.

The story, as I mentioned earlier, begins with an unprecedented creation of wealth by Netscape IPO, which set the groundwork for the reality of the modern Internet era. Before Netscape, there was Tim Bernes-Lee who essentially created the web and open-sourced his baby invention to hundreds of eager developers willing to put in the effort into crowdsourcing the “future.” Soon the X Mosaic was born, the first real browser. When the founder of Mosaic, Marc Andreessen and the ex-founder of Silicon Graphics, Jim Clark came together, Netscape was born, and Netscape was the first true dot-com, which blazed the trail for other Internet companies and set a standard for modern tech startups.

But we all know how it ended: Bill Gates was nowhere receding his dominance in the computer industry. With Windows 95, Internet Explorer entered the home of every American. There was no need to download or pay for the Microsoft browser which was a very significant advantage over Netscape’s Navigator. And by 1997 Internet Explorer seemed to win the arduous battle.

The story then unfolds into numerous details about the early businesses on the Internet and how they came up with ideas to stay on top of their competition, gain readership or followers. In particular, McCullough relates the story about my favorite publication back in the day, called Slate, and how it became one of the prominent pioneers of professional online content.

In chapters on The Early Search Engines, the author talks about unprecedented parabolic growth of Yahoo, and how the company came up with an idea of a web directory and a business model of making money from the ads around that directory. By 1997 the online advertising market reached one billion dollars, with companies competing viciously for the prominent placement on the Internet’s first Yellow Pages.

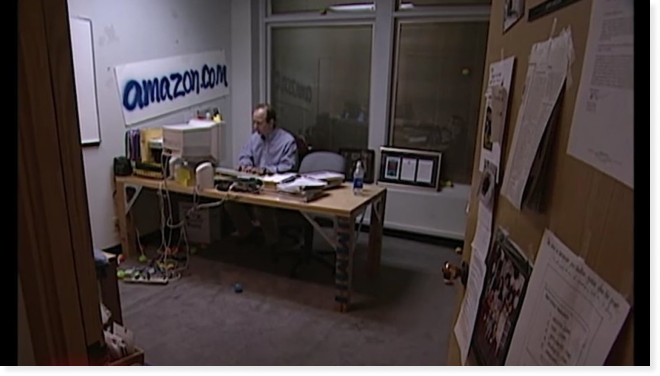

Among those early competitors was — you guessed it — amazon.com, who symbolized the advent of the net’s big e-commerce era.

Amazon’s story begins with a twenty-eight-year-old Jeff Bezos who came up with an idea of “everything store” back in 1992 when he was still employed at the hedge fund of D. E. Shaw. As proof of concept, he decided to start selling books first. By 1994 he no longer worked for D. E. Shaw: he left a lucrative career for some uncertain prospects and an idea. Well, we all know how it ended. Jeff Bezos is the richest man on Earth with his net worth surpassing 135 billion dollars. Obviously, selling books was a great idea.

Reading how it all turned out for Bezos is some very riveting and emotional ride: a couple of times I got goosebumps all over my arms just by imagining it in my head that a “whiz-kid” programmer went that far: from a badly heated garage space with no business plan to the largest business in the world with a share in virtually every market. Bezos never seemed to care to make it big in “books.” From day one he knew what he truly wanted: take bigger bites of other markets until he had “a piece of every market.”

McCullough also makes an interesting observation that while the Internet happened in Silicon Valley, to its largest extent it was monetized by startups in the East, namely in New York City. Silicon Alley became a sobriquet for the area around and below Madison Square Park and the Flatiron Building, where a dozen or so tech startups sprang up like mushrooms after a summer rain.

Thanks to Sergey Brin and Larry Page we no longer have to deal with irrelevant search results. These guys came up with PageRank, a search engine that combined the algorithm prowess with traditional strategies of information retrieval backed up by its relevance. PageRank was so powerful that it could actually even answer the question. The funny thing is that not many people know that before trying to make a company out of PageRank, Brin and Page tried to sell the idea to major search companies, like Yahoo, InfoSeek, Excite. No one seemed interested except Excite who said it was willing to pay $750,000, which Brin and Page (thankfully) declined. A year later, Google was born.

Now the dot-com bubble didn’t just happen out of nowhere, it had very specific reasons and events that gradually led to its burst. Hundreds of new technology stocks debuted in the late 90s: some of those stocks were backed up by nothing and their value would skyrocket even if the company announced losses. Fortunately or unfortunately, through such a natural selection process, only the greatest and most capable survived.

After the bubble burst, it was Steve Jobs who came to the rescue like a Batman or Superman. But his first mission, though, was to save his own company, which was on the verge of bankruptcy at the turn of the century. iPod was what reanimated Apple and brought it back to its senses: an unmistakable aesthetics, minimalist design, genius feature wheel that allowed users to seamlessly browse through their music instead of continuously pushing the buttons. The simplicity of the device turned out to be a genius idea. The iPod became the antecedent of the whole new era of digital music, which was later amalgamated into a new phenomenon of iTunes.

The book unfolds into numerous minuscule details about the other startups that were popping up during the early 2000s — some of them no longer live, but some others turned into behemothic tech ventures, among those are PayPal, YouTube, Wikipedia.

And then there was Facebook. The pioneer of Social Network era.

Thankfully, the tone of the narrative that McCullough employs in his writing is neutral: the author doesn’t give any particular editorial omniscience or share his thoughts on the main characters. McCullough just relates the straightforward sequence of events without going into much speculation over the described individuals’ “rights or wrongs”.

This is exactly why you won’t find the author’s attitude toward Zuckerberg, Jobs, or Bezos.

The book ends with a chapter on the iPhone and its present dominance. We all remember how Steve Jobs used to somberly enter the stage and with his characteristic panache say something like “Every once in a while, a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything.”

Makes you wonder, that we are truly living in an interesting time. I would not swap in a lifetime the time I am living in for something else, neither future nor past.

Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future | Peter Thiel (2014)

Peter Thiel’s book is something different from the two books above in a way that it attempts to teach how to build successful startups or create new prominent things. It might be an ideal read for any new aspiring or seasoned entrepreneur who is willing to learn how to survive in a gigantic world of bureaucracy, lack of proper talent, and scarcity of genuinely new break-through ideas.

Peter Thiel is not just a creative non-fiction writer, he knows what he’s talking about: Thiel is the co-founder of PayPal, a powerful investor who infused tons of money into hundreds of startups including such tech giants as Facebook and SpaceX.

From the very first chapters Thiel makes a couple of powerful conclusions that aim to teach a lesson from the dot-com crash:

— Make incremental steps: if you want to change the world, you’d better be humble and do your job in disguise until you’re ready to share it with the world. However, remember that it’s better to be bold than trivial.

— Stay lean and flexible: instead of planning, try things out, experiment, iterate. However, remember that a bad plan is better than no plan.

— Learn from the competition: instead of creating an entirely new market, start with an existing real customer and improve on the existing products. However, remember, that competition destroys profits.

— Make your product great first: instead of thinking how to sell your stuff, think how well you should develop your product and develop it well. However, remember, that sales are just as important as the product.

Overall, Thiel makes all of his arguments around controversial ideas that challenge traditional thinking and make you think outside of the box. Every time he introduces the concept, he looks at it from different angles and gives hypothetical or real examples.

Thiel advises concentrating on building a monopoly when starting the company. Because too often startups think of short term growth rejecting the bigger thinking. The author proposes the following solutions:

— Create or develop proprietary technology, because it’s the only main guarantor of long-term growth and the greatest substantive advantage a company can have because it makes your product virtually impossible to replicate. A good rule of thumb is to make something 10 times better than an existing technology or, otherwise, create something completely new.

— Network! The power of a network is when you sign up for a service when everyone else is there already. However, to build a network, start small. Zuckerberg initially created a network for his classmates, not the people of the entire Universe.

— Get stronger by getting bigger. Twitter didn’t need a lot of features to add up for millions of users to join in, because the idea behind Twitter already had a breakthrough notion that allowed for economies of scale.

— Branding is important but much less important than proprietary technology. Thiel gives Apple’s example when awesome design and luxurious stores can be replicated, but Apple’s technology is still far more superior than of its competitors.

Peter Thiel is sometimes overly philosophical and tries to explain his pessimism for China with some fancy Plato and Aristotle terminology. By the end of the book, it becomes obvious that the author is fervently in love with his own country and preaches the American dream startup culture for every other country in the world.

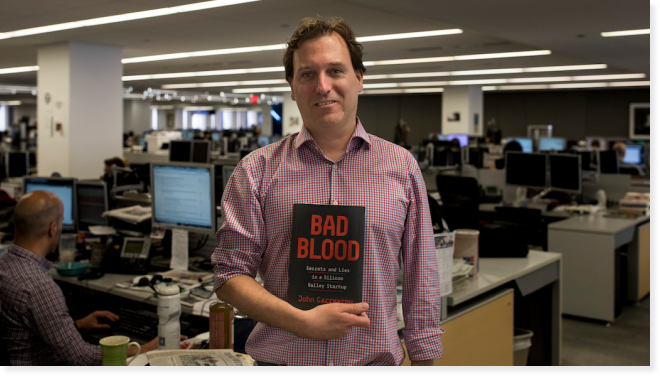

Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup | John Carreyrou (2018)

Bad Blood is not your conventional non-fiction, it’s a captivating psychological thriller full of suspense, treachery, fraud, surveillance, and intimidation. It’s even more riveting and unbelievable because it’s hard to get your head around an idea that it is actually a true story.

Bad Blood is written by the Wall Street Journal’s renowned investigative journalist, John Carreyrou, who relates a story of a mythically mysterious startup from Silicon Valley, called Theranos; and its charismatic young leader, Elizabeth Holmes, 22, who created the company upon a lie that health information could be obtained by a small drop of blood through handheld devices. Carreyrou writes the book after having interviewed more than 150 people some of whom preferred to remain anonymous for fear of retribution.

The story starts from describing how Elizabeth, although being super young, built up a super all-star cast team around her, from Henry Mosley, Silicon Valley veteran, to Donald L. Lucas, the venture capitalist, who helped make Oracle corporation public. Nobody, however, knew exactly how the thing was supposed to work. So how Henrey Mosley recalls it, whenever someone asked him about how the blood thing worked, he would go with them to Shaunak Roy’s lab, Theranos’s co-founder, where the latter would perform magic tricks from pricking his finger and running a blood sample through so-called “reader.” Unbelievably enough, the screen always came up with a result. The believable thing was though, that the screen showed a prerecorded result from the only few times when the machine seemed really to work. When Henry Mosley found it out and brought up to Elizabeth, she simply fired him.

John Carreyrou, through a third-person narrative, describes how Elizabeth possessed an almost mystical animal magnetism and charisma: she could hypnotize anyone with her clear blue eyes and unusual mesmerizing voice of a baritone. She was a zealous admirer of Steve Jobs and deliberately copied his style both in how she dressed and how she tried to manage her company.

Her animal prowess was the exact reason Theranos had been able to attract millions of dollars in investments and convince pharmaceutical giants of the viability and sustenance of the blood testing system. The reasons why CEOs of big pharma companies so readily believed Elizabeth was the promise of the new software cutting their costs by 30% because it hypothetically allowed to reduce the time for clinical trials.

Theranos experienced a spectacular rise: by the end of 2010, the company had acquired more than 92 million dollars in funding. San Francisco Business Times said Holmes formed “the most illustrious board in the US corporate history,” partly because apart from the famous venture capitalists, her company was backed up by the former Secretary of State, George Shultz.

By 2014, Elizabeth made it to the Fortune 400 list and appeared on the cover of the major publications like Forbes and the New York Times. Her net worth was estimated at 9 billion dollars. In 2015 Holmes made numerous big deals with such pharma giants as Cleveland Clinic, AmeriHealth, Walgreens, and others.

John Carreyrou describes in great detail how Elizabeth built up a secrecy culture inside Theranos: how she made everyone sign non disclosure and non disparagement papers; how she instructed employees not to make eye contact with the board members; how she fired those who didn’t agree with her; how she made people aggressive, oppressive, and hostile to each other. Having just written that, I realized how such a great story (nevertheless absolutely horrific) would make for another breathtaking season of American Crime Story.

Carreyrou also depicts deeply engaging portraits of the major characters of the whole Theranos business, whom Elizabeth surrounded herself with, like Sunny, an affluent and vain Indian boyfriend; but more so, told the stories of people who initially believed in Elizabeth and then over the matter of years or months and sometimes even days, discovered the truly sinister nature of her persona and the totality of a lie underlying Theranos business.

The story delves deeper into bureaucracy and the importance of high-power political connections that govern the deals in Silicon Valley and tries to undermine the present state of events by exposing corruption, intimidation, blackmailing and false claim allegations and litigations that contributed to the rise of Theranos.

Overall, not to reveal any spoilers, I should only disclose that this book turned out to be a page-turner; an absolutely riveting story that reads from the very first to the very last page on a single breath.

Stealing Fire: How Silicon Valley, the Navy SEALs, and Maverick Scientists Are Revolutionizing the Way We Live and Work | Steven Kotler & Jamie Wheal (2017)

The last book we cover here is the most controversial piece of literature I’ve read in months. It’s also the most contentious on the list. Perhaps, you’re familiar with recent revelations about the dark side of Silicon Valley, thankfully unrelated to corruption and bureaucracy exposed by the previously discussed investigative piece, but that concerns the madly obscene off-hours of some of Silicon Valley employees. From what I’ve read and heard before stumbling upon Stealing Fire was that the male demographic of Silicon Valley has recently started the underground culture of sex-laced and drug-fueled partying. And although Elon Musk has denounced the brotopia culture by saying the bunch of sex dorks were nothing more than “nerds on a couch,” it’s still interesting to see or read how other people (especially smart) make their unconventional lifestyle choices.

This book, however, takes a slightly different stance, on that it propagates the use of (sometimes?) illegal substances to alter the state of consciousness. It opens up with a pretty promising message saying that a lot of people have already been using these “ecstatic techniques;” among those who tried the stuff, the author mentions Silicon Valley executives, Wall Street Traders, military officers, and scientists.

In particular, the story alludes to the famous art project, Burning Man, as the most obvious showcase of this revolutionary thinking. For example, the author relates the story of Page and Brin making their hiring decision for the CEO of Google partly on the fact of the prospective candidate’s attendance at the festival.

With kind of short but representative chapters on neurobiology and pharmacology, the authors provide some scarce examples and scientific data on the harmless nature of low doses MDMA and LSD, claiming that tobacco and alcohol are more serious culprits to the human overall wellbeing, whereas the aforementioned drugs are supposedly beneficial if taken in low quantities, so-called microdoses.

While it is certainly an engaging read, it’s hard to ascertain the claims the authors make, thus of legalization of those mind-altering drugs and some other shady practices of transcendental sex.

Conclusion

Bad Blood, from those described books, was my favorite. It’s a fantastic piece of investigative journalism that confirms the premise that getting to the bottom of the truth is always worth a long shot. It’s an outstanding job that John Carreyrou performed under such extreme circumstances of pressure, bullying, intimidation, and scaremongering practices that Theranos and its management employed against him.